A forest fire is coming to American Science

Sometimes a big change is easier than a small change.

The night before the election, I shared who I was voting for. I riffed on the Harris campaign’s refrain of “saving democracy,” arguing that saving democracy is more about how we interact rather than who we vote for. It’s more important to be human and connected than ever before. Still, my choice of Trump shocked a lot of people. I received many private messages in response, the vast majority were positive or at least curious. The most constructive conversations normally started with a “I deeply disagree” but ended on an affectionate note. If the conversation really went well, the last thing people would ask me is “Dan, what makes you optimistic about this new administration?” Here is my answer.

Four days after the election, I’m walking through the Weir Hill nature reserve and found the metaphor for American Science in 2025. Weir Hill “restores their habitat with fire.”

In contrast to forest management to prevent wildfire, which have led to static ecosystems becoming tinderboxes, Weir Hill takes the opposite approach to cultivate dynamic, young ecosystems."Without active management this area would succeed to mature forest, and this rare habitat and wildlife that depends on it would disappear." In the northeast, the result of fire is transient blooms of wild indigo which then host beautiful species like the Frosted Elfin Butterfly, endangered because of the lack of natural burns. In other forests, it takes fire to releases seeds from the pinecones to grow into the next generation.

We all know a forest fire is coming to science. I believe we can make this a good thing.

Some of the old growth of our academic ecosystem is beautiful and essential, yet just like in a badly managed forest, the broader ecosystem got stuck in an artificial stasis. If science progresses one funeral at a time, then maybe nation-scale science progresses one DOGE at a time.

Like everyone else, I’m getting my own bearings and developing my mental models for a volatile few years ahead. Before getting to science problems and possible solutions, it’s worth being grateful for an uncontested election and appreciating the path not taken.

Let’s be thankful that we got one of the two best outcomes in the election

Trump getting elected is not the end of the world, but Trump being killed on the campaign trail would have been the end of our world as we know it. I don’t think this is appreciated widely enough. We missed civil disaster by inches and all we got was the most iconic political photo in my lifetime.

The two best outcomes were a landslide victory for Trump or a landslide victory for Harris. Anything else would have been dragged into court, raised claims of fraud, created more online hysteria and decreased confidence in the democratic system. Worse, there would have been reputational damage done to the US at a time of increasing multipolarity, which would have hurt the investability1 and leadership capacity of the US.

Peter Thiel had a memorable on-stage comment over the Summer when he was asked if he’d engage with the politics in this election. Paraphrasing, “I’m going to sit this one out because I have nothing to add. If Trump wins, it’ll be a landslide. If it’s close, Harris will win by cheating.” After some gasps, half the audience booed, half the audience cheered. That’s 2024 politics encapsulated in a 30-second exchange.

Thiel was right. Trump swept all seven swing states and won the popular vote by 2,475,506 voters. Riding Trump’s popularity and discontent with the Democratic incumbents across the board, the House, Senate and Governorships also went red. This is clear victory, likely the most dominant and odds-beating election in my life, but what matters most is that it’s done and we can move on.

The big story is individuals over institutions

A few years ago, following a prompt by Tyler Cowen, I wrote the essay “Is the world getting harder to predict?” I concluded that yes, the world is getting harder to predict because although large organizations are easy to model, individuals are not, and it’s individuals that are increasing in power. Worse, larger institutions like universities, the NIH and national political parties (DNC and RNC) are both increasingly predictable AND dysfunctional.

Kamala Harris was always just a representative for the Democratic Party. She refused to do anything that define herself as an individual beyond her institution. So this election was a head-to-head of two very different teams: On the blue team, the Democratic National Convention, a billion dollars, legacy media, and academia. On the red team, Trump, Vance, Elon, RFK, Tulsi, Rogan, Thiel, Tucker, Vivek, Lonsdale and their respective empires. Team Blue ran the predictable same plays as the previous two campaigns. Team Red did weird things and spoke their minds. Team Red won bigly.

The individuals vs institutions dynamic is going to play out first in government agencies then in science. The biggest trees —the biggest, oldest government science institutions— are going to burn the hottest. But on the other side, we may have an innovation ecosystem that empowers, rather than stifles, the individual.

Talk to professors today, and they’ll tell you the situation today is untenable: flat science funding, sky-rocketing costs and an ever-lengthening path to career stability. Creative destruction is necessary, and sudden jolt is needed to break the inertia and get us on a better path. Without such disruption, we risk following the troubling trajectory of similar countries.

A Harris presidency probably would have mirrored the inertia of other countries

It’s fair to say that a Harris presidency would have looked like our more liberal, institution-centric allies. Canada and Germany, for example, look smart but they are not doing well. We don’t want to be like those countries right now. As I said in the last blog post, “Maslow is real: Climate policy means nothing if we have a failed currency and unsafe place to do the work.” Consider:

Climate sits inside of science,

Science sits inside of an economy,

An economy sits inside of a functional and safe country.

Put coldly, if there is ever a World War III, nobody will care about CO2 levels in 2080. A vibrant science ecosystem can only thrive with sufficient funding and stability to look ahead.

Negative GDP growth may be less hyperbolic than nuclear war but it has the same impact of squashing the long-term, ambitious spirit that gets people in science (especially climate) in the first place. If the people are unhappy, or if the government has to shut off the power to universities to curb rampant inflation (as is happening in Argentina), science is the first to go.

Canada is a yellow warning light: Canadian GDP has grown a paltry 4% in the past decade (the US has grown 47%) and now the cuts are coming to Canadian science: among others, ~20% off the Canadian version of the SBIR despite the government’s own figure that every $1 into that program produces $3.10 of GDP and $1.40 of tax revenue. How bad are things if they are cutting programs that pay for themselves?

Canada can fix their issues but Germany seems to be a full-on goat rodeo. It’s likely going into a depression due to its inability to adjust course from institutional inertia. And this one feels personal to me.

In 2018, new President Trump went up to the UN podium and said “Germany will become completely dependent on Russian oil if it does not immediately change course.” The Germans mocked him and this moment went viral in my networks along the lines of “look how embarrassing our President is!” I remember watching this moment in lab and feeling the emotions clearly: we in biotech academia all looked to Germany as the country of smart people. But six years later, Trump was right and those German leaders have been horrifically wrong.

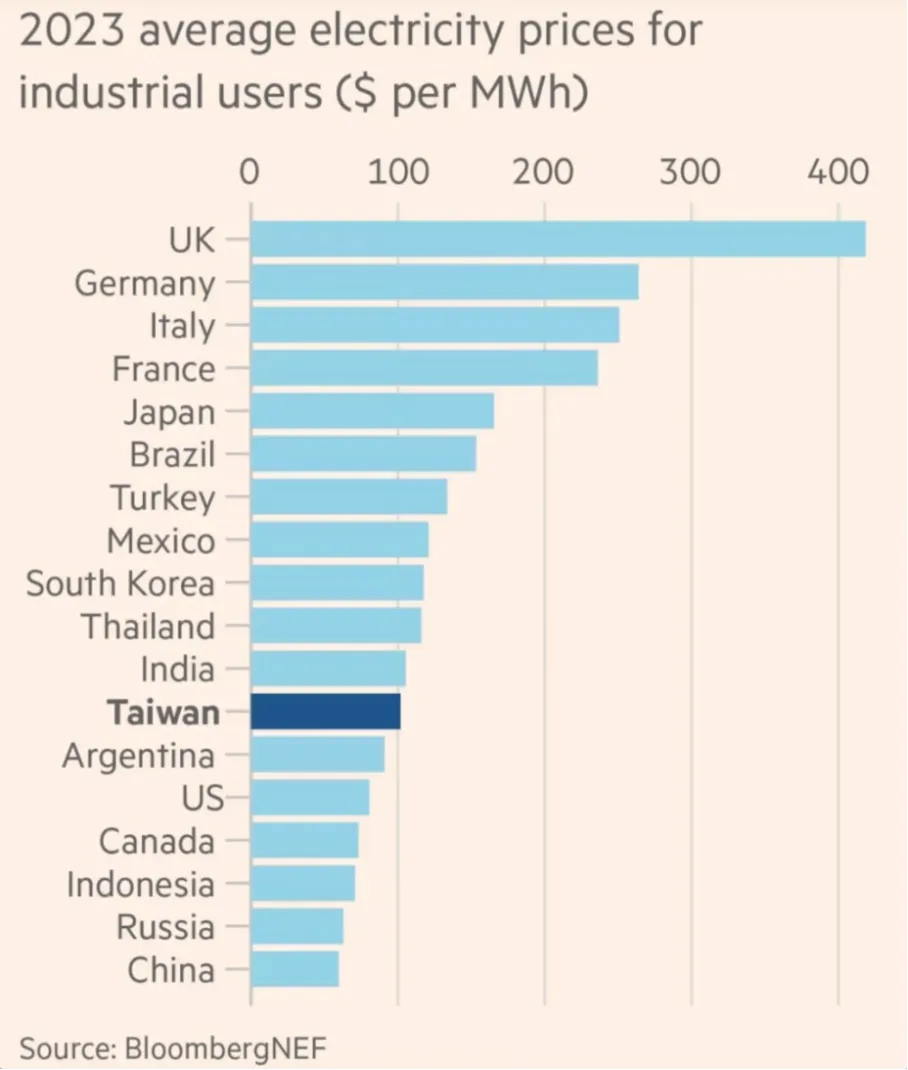

It would have been bad enough if Germans were “just” stuck on Russian energy since the war started as Trump warned. But astonishingly, the progressive Germans still proudly dismantled their nuclear energy capacity, an own-goal on 25% of their baseload power, in the middle of an energy crisis due to a kinetic war next door. This was institutional arrogance mixed with corruption: only 25% of the country actually wanted this. The dominos fell: Energy costs tripled, government subsidy programs vanished with tax revenues, green technology factory plans got scrapped because nothing could be made profitably in that environment, the government hit their Debt Brake. In a Murphian comedy, there was no wind in Germany’s sails the week Trump got elected: wind power vanished leading to blackouts despite the €500-€750 Billion Energiewende electrical grid overhaul. So Germany’s coalition government collapsed then they dropped out of COP on November 7. No matter how polished, no matter how passionate the climate rhetoric, Germany’s capacity for global impact is minimal until massive changes are made.

It’s more than just Germany: Europe’s trends are so bad that the EU commissioned former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi to analyze the stagnation. Noah Smith does a pretty good walkthrough of the 328-page report, and it’s bleak and contains themes of institutional bloat. Back in the USA, the domestic Overton Window is shifting rapidly: Nate Silver just roasted the Expert Class in the US and Matt Stoller’s anti-monopoly blog aligns more and more with Trump’s appointees. I would not have expected these outcomes in 2015.

So I think another Democrat Institutional President doing more of the same would have kept us in the boat with Germany, the UK and Canada. There would have been some superficial changes to address some problems in science. And maybe some sweeping Executive Orders from President Harris, maybe some billion-dollar programs. But I think they all would have been small perturbations around the same negative trend. As my wife once said, “sometimes a big change is easier than a small change” and I think only a big change gets us onto a positive, long-term viable path.

Here are nine problems of science in 2024

Applied Scientists are the most powerful people in the world.

This will be more obvious in the coming years. -Naval Ravikant

Everybody agrees that our science must be excellent, and everyone agrees it could be a lot better than the status quo. I like Eric Schmidt’s term Innovation Power — “the ability to invent, adopt, and adapt new technologies” — when he argued for Innovation’s importance to a country’s hard and soft power. But before we can start to pitch solutions, we have to start framing problems with our current innovation ecosystem:

The USA sends ~$54B/year into universities for research despite 90% drop of return on investment (evaluated on disruptiveness) since 1980 and majority disapproval of universities. Less than half the country trusts universities, likely because of excessive politicization, and approval numbers continue to drop.

At least one third of degree tuition, $130 Billion per year, is wasted on degrees that are worth less than their price tag. What would you study at Boston College if you were paying $92k per year at a school with no merit-based scholarship?

Elite academia has become an exclusive and brittle monoculture. DEI and Covid origins are two well-known examples of a tightrope of acceptable discourse, marked by aggressive self-policing. Two good (long) essays of the status quo are from Claremont McKenna College and from Stanford. Administrators continue to hockeystick - MIT hired 6 assistant deans of DEI in 2021. Prestige is an unstable equilibrium: once you’re no longer the best, the fall is steep.

Universities are progressively failing to recruit and maintain top talent. Top academics are leaving for 10x salaries at industry labs. Chinese nationals are going back to China at an exponential rate, top graduates just go straight to industry. The starting salary as a professor at Harvard is $125,000, which is barely enough to raise a family in the area, and comparable in pay to a lower-stress administrator job.

The awfulness of postdoc and early professor life scares talent away from science. Only ~20% of postdocs get faculty jobs. Then Professors spend 40% of their time applying to grants and are stuck in their lanes despite wanting to branch out (Fast Grants Survey). This is why many PhDs drop out to work in data science or parlay their grad school acceptance into a financial services job.

Venture Capital outcompetes the government for superstar talent for advanced research funding. When DARPA were invented in the 1950s, Janet Yellen (today’s Treasury Secretary) would have earned more than David Solomon (CEO of Goldman Sachs). Today, David makes 100x Janet’s salary. You can’t blame young talent for wanting to be David, not Janet. Or, in technology, young stars want to be Sheryl Sandberg, not Evelyn Wang (ARPA-E Director).

The US has created ONE elite university since 1955. There have been good state schools, but the energy and investment to create a great school, like a Stanford (1885) or an MIT (1861) or a Harvey Mudd (1955) or Olin (1997) just isn’t present right now.

The American innovator is stuck with a duopoly of universities or startups to develop her technology. As I explored it the Problem-Centric Founder, startups and universities do *not* span the whole space of needed work. A defeatist “There Is No Alternative” mentality to funding scalable research at places other than universities.

Philanthropy has been leading the experiments with scientific ecosystems but it’s a bridge to nowhere until the government learns to work with these new organizations. Ben Reinhardt’s “Fund Organizations, not Projects” 2022 policy piece articulates and addresses a pain which all philanthropically-backed organizations feel. Cultivating the founder phenotype in science can be an unlock for science, but that requires building an ecosystem with full organization lifecycles from seed checks to acquisitions.

Here are three ideas for science

The first phase of the Trump II Presidency is probably going to be focused on cutting rather than building. Still, there’s a natural appetite for seeding positive action in the first 100 days of a presidency. For innovators with their own sources of capital, this can be a high-leverage opportunity window to work with, rather than work through, the government. And once the forest fire settles down, there will be sunlight for new ideas to grow rapidly.

Here are three kernels of solutions to the problems:

1. Create a government fund that moves at startup speed

The institutions vs individuals dynamic will play out in science. This is good because we need more startup-like energy and less organizational drag. Funding will always be the crux. We need mechanisms that combine venture capital's agility with government-scale convening and purchasing power. We could create a Fund for Accelerating Applied Research, matched by philanthropy and private money, which leverages existing fieldbuilding organizations to discover, cultivate and support teams of practitioners. For more information, see: Academia 2.0 Can look more like startups.

2. Empower the Progress Studies movement

There is a vibrant, organic community that studies the people and forces behind great leaps of progress. Nobody anointed them or certified them, they are independent writers and young organizations that just got to work. At first I ignored them, but I’ve come to love them because engineering growth in target subfields is inherently a Progress Studies challenge. We need to formally recognize and fund this emerging field of Progress Studies, creating an official platform for that includes voices like Jason Crawford (Roots of Progress), Nadia Asparouhova, Alec Stapp (IFP), Eric Gilliam , Kanjun+Michael (Science++) and other leading thinkers.

3. Launch experiments toward elite universities 2.0

Instead of fiddling with who gets into Harvard, we need to build new and better Harvards. America's failure to create elite universities in the past 70 years is an embarrassment. We must embrace the uncertainty of education in the post-AI era by encouraging broad but substantial experimentation. While President-elect Trump's proposed free online American Academy sounds awesome, we also need new models for intensive, hands-on training of elite talent.

Conclusion: Adapting at Technology's Pace

In the AI era, any organization that can't keep pace with technological change is doomed. Large institutions are naturally disadvantaged in this race condition, but when an organization can be both big and nimble, then you get a generational performance like Amazon’s pivot from books to compute.

While America's scientific enterprise remains anchored to universities and federal labs, we have an opportunity to build something better. Through federal reform and ecosystem development, we can create problem-focused, founder-led research organizations that outcompete the status quo on cost, accountability, and speed to discovery.

The forest fire is coming. But like the Frosted Elfin butterfly or the seeds of a lodgepole pine tree, some of our most beautiful innovations might be ready to emerge.

Hidden Forces had an excellent episode with online investor personalities Paulo Macro and Le Shrub in which Paulo shares his view of the “EM-ification” of the West (EM = Emerging Markets). The core point is that when economic and cultural policies of a country whipsaw between extremes depending on elections, it scares away long-term investments. This is the “doom spiral” of many struggling Emerging Market countries and is a real risk to the Developed Countries that can’t calm down their political divides.