Exploring Impact Certificates

Could a new certificate make funding public goods as successful as venture capital?

This time last week I was jotting down notes in a hotel after an amazing two days at the Funding the Commons conference organized by the Protocol Labs. There were many great experiences and new connections made, but two highlights stand out: It was our public debut of our non-profit Homeworld (“Hello, (home)World!”), and the first time I began to see potential in this wild idea of Impact Certificates.

First, If you are interested about Homeworld, you can see my talk on behalf of our community, and screenshots of highlight slides, in Vincent’s tweet below. While most people at FTC22 were talking about platforms, I was talking about content that might one day utilize such platforms. This dynamic made for many great hallway discussions, including the idea of Impact Certificates.

The idea of Impact Certificates goes back to 2014 in the Effective Altruism forums. Going through those old forums now, the ideas sound interesting but wouldn't have stood out to me (an outsider to the EA community) as particularly groundbreaking. But Juan Benet’s talk presented a very cool viewpoint which stuck with me as compelling and worth further exploration, especially from the perspective of trying to fund early stage biotech projects for the public good of climate-positive tech development. Again, Vincent’s tweet is a good entry point:

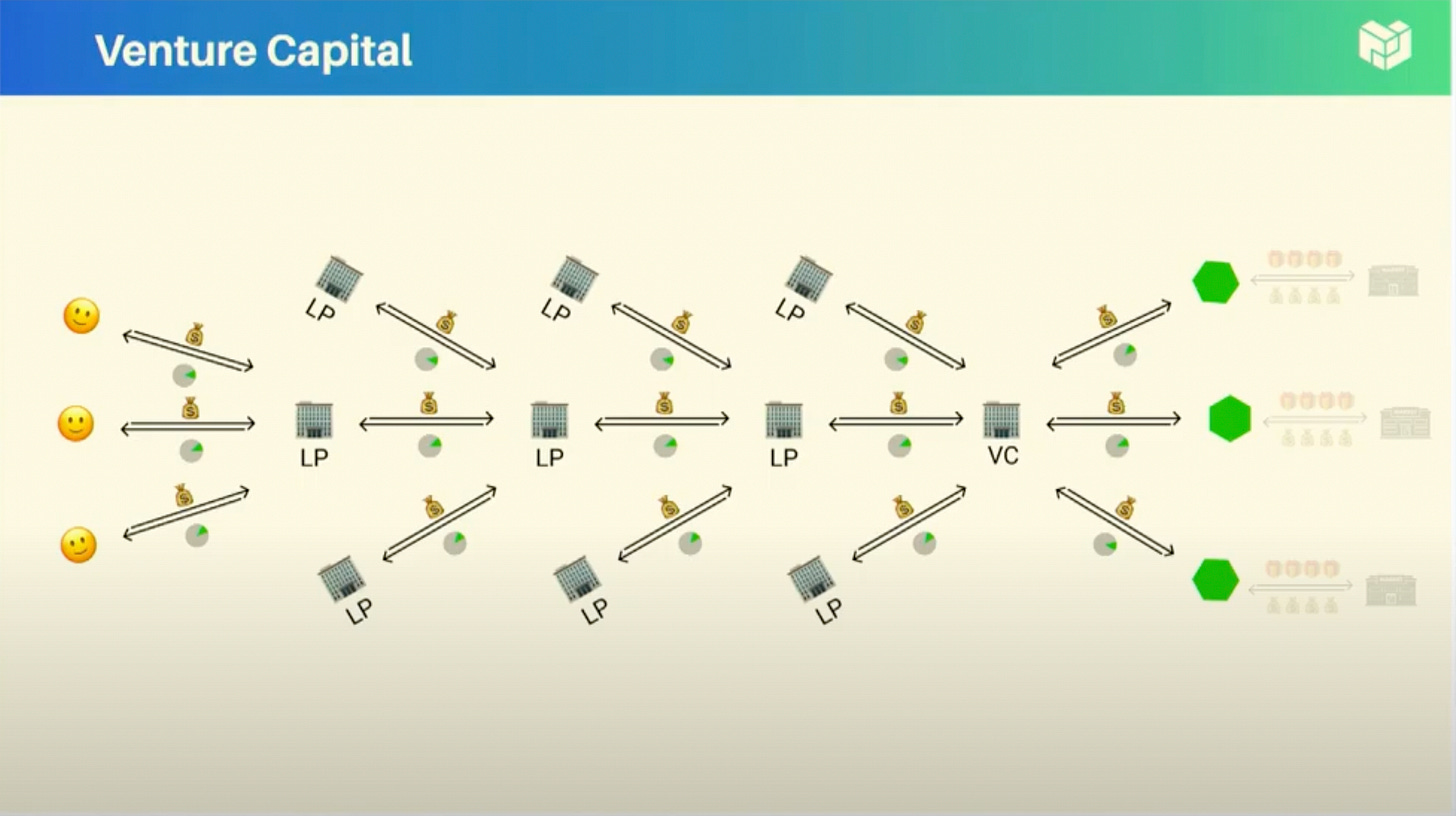

Juan’s talk explores why the venture capital (VC) model has worked so well well1. One reason is that the VCs who make the actual investment into a company tend to be close to some aspect (technical, social, etc.) of the projects that they fund. The VCs exchange stock certificates for cash with the startups, and then the VCs pass the stock certificates onto their own investors who then have their own investors, etc.. It is non-obvious that more steps in a network is a good thing: why would all these intermediate steps between the company and the original sources of the capital make sense?

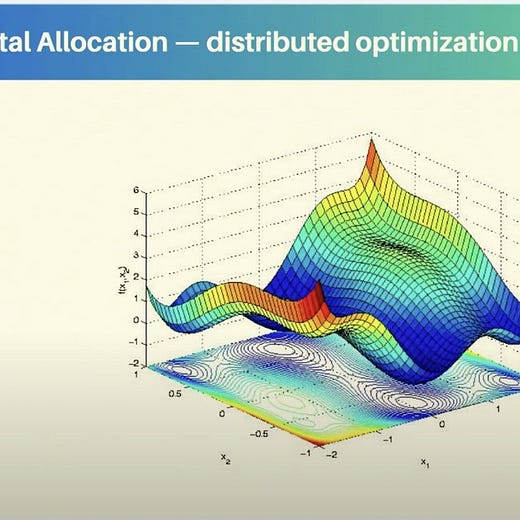

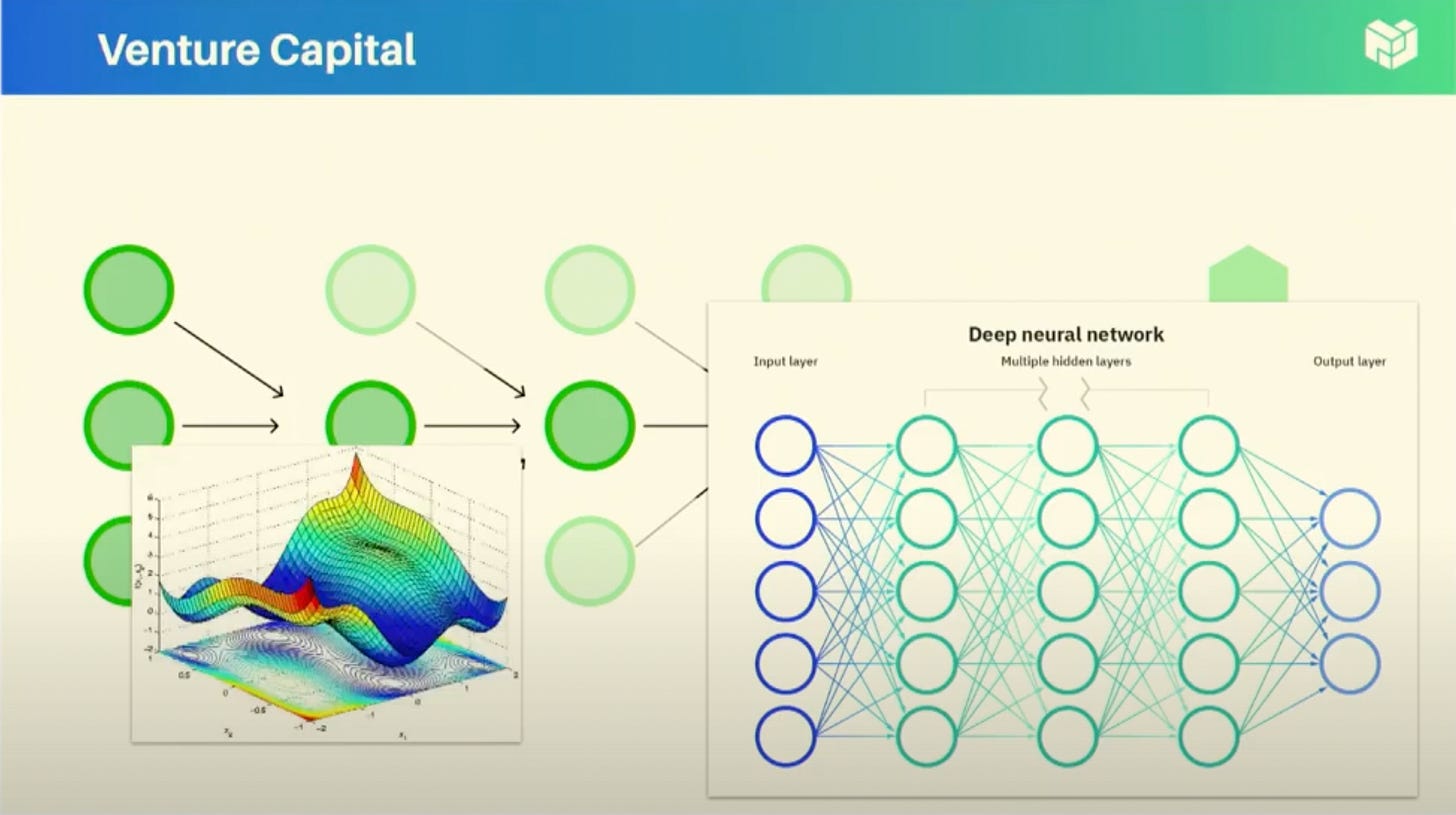

There is a topological argument of why this VC structure is powerful. Juan points out that this looks a lot like the composable learning units inside a deep neural network. Deep nets excel at learning complex solution surfaces at multiple scales (ie, broad trends vs tiny details), which Juan further illustrates in the slide below.

Composability enables multi-scale learning and execution, which is what enables financial behemoths like the state pension funds to profit from young startups. Let’s use CalPERS as an illustrative example: their $470BB fund gets distributed to different managers with diverse theses, some of those managers invest into VC funds for their diverse sub-industry specializations, and finally each VC finds+supports the best startups for their given zone of competence. Profits are ultimately returned to CalPERS via stock certificates, irrespective of how many intermediate layers. There is indeed a commission paid each node hop between startup and primary funder, but the costs are a tradeoff for distributed sector expertise. For playful contrast, imagine a CalPERS employee going through Hacker News forums in an attempt to deploy $1Billion into startups: that money would get vaporized with no meaningful impact. Hence, the composable funding structure, enabled by the (eco)system of stock certificates, facilities large amounts of capital to be matched with expertise that finds good allocation opportunities. It is certain that, regardless how indirectly, money from enormous funds have been responsible for expanding the frontiers of science and technology.

The composable funding structure then sounds like a good idea, so the natural followup is to ask why it is not deployed in every funding environment. In the absence of profit incentives or financial infrastructure, the stock certificate (eco)system does not apply and composability feature breaks down. For example, if you were a Gates Foundation grantmaker with the mandate of saving lives via malaria medication (a very different mandate than the profit mandate at CalPERS etc.), you would likely be directly funding the organizations who distribute the malaria medication themselves2. This is because you would need to validate that you’re funding is actually reaching its intended impact. So, if you had $1BB to spend in a year, you would just be talking mostly with the entities most credibly ready to spend it immediately in an auditable way, which then may force too much money into the limited pool of candidate entities to fight malaria. Should you instead try to go through arbitrary numbers of middlemen in a foreign country in a vain attempt to replicate the like the CalPERS example above, you lose oversight ability and would feel at high risk of being lied to. How would you have any second-hand trust in an organization that you’d never met or validated yourself? How would you report your performance to your boss?

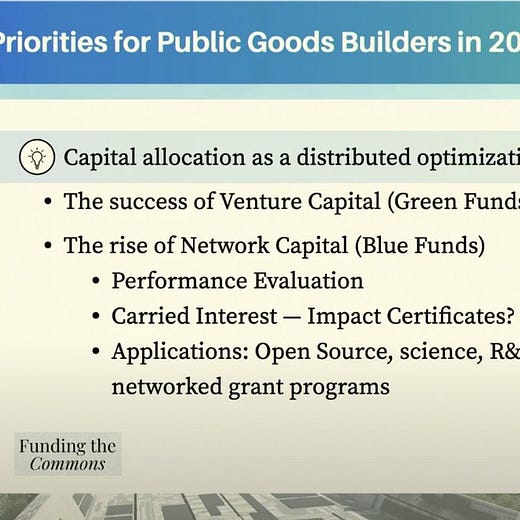

The bold idea to explore is what if impact certificates could be the non-profit version of stock certificates? What would it take for a certificate to enable the same efficiency of profitable investments into the public good investments? Juan suggests three features to start:

Feedback: The performance of the underlying asset is the same for all holders of the certificate. Information has to propagate through the network in order for the ecosystem to improve.

Transferability: The certificate is able to be passed throughout the funding ecosystem

Fractionalization: The certificates can be split up for compensation and reselling.

Before going into my scientist’s perspective questions on what Impact Certificates might need to work in our domain of biotech, it is worth unpacking two other talks from Funding the Commons that articulate the aspirations of Impact Certificates.

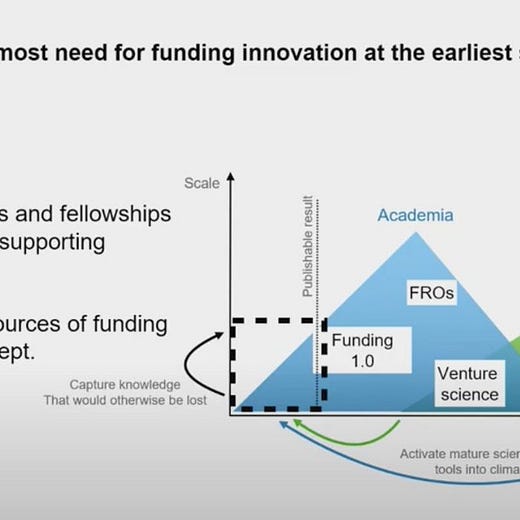

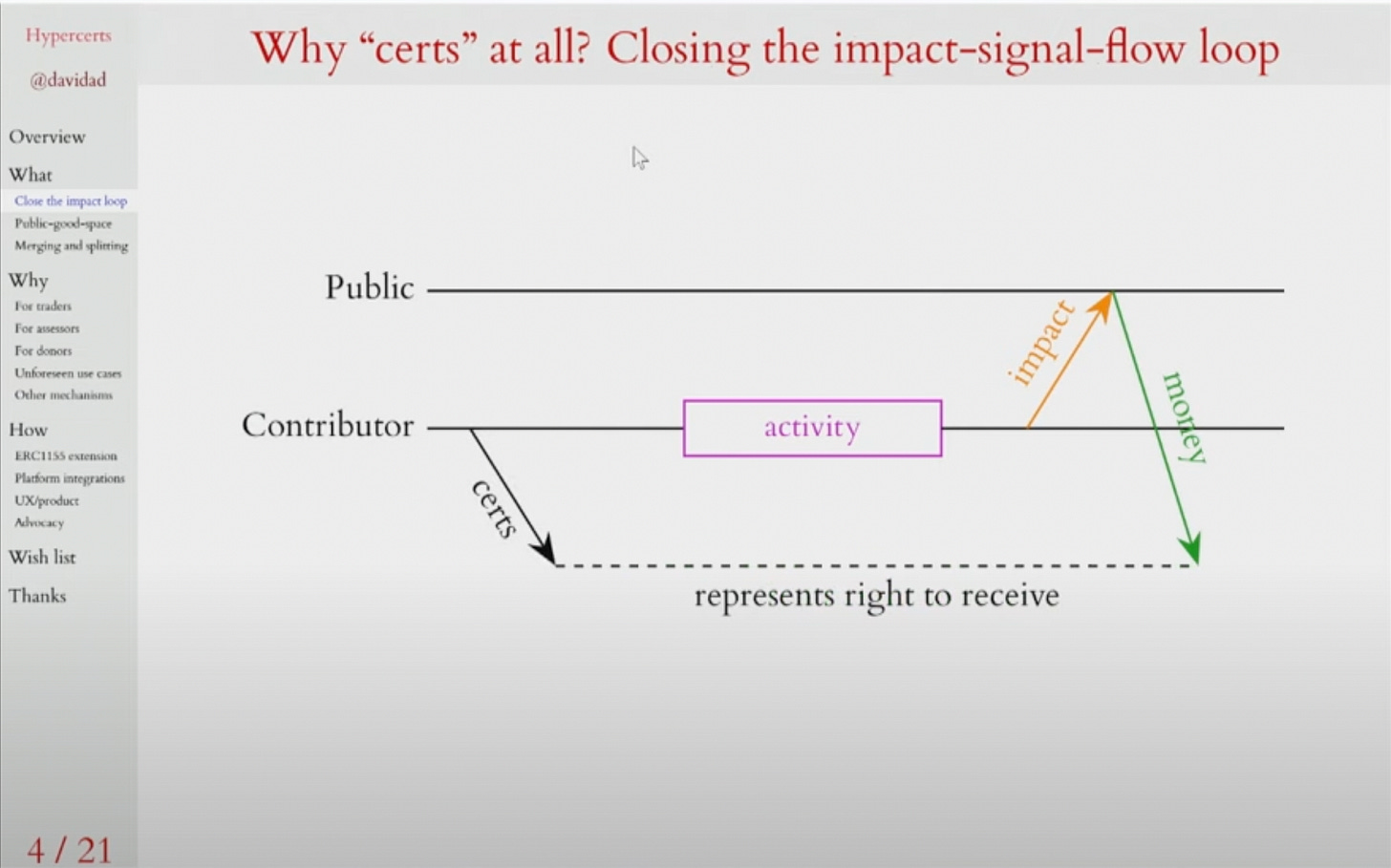

David Dalrymple pointed out in his FTC22 talk on “hypercerts” that there is a temporal component of impact certificates. If a public good task has been completed, then there is no reason for a funder to pay for it: As on explantation for why this is the case, consider that there is no additionality in funding something that has already been done. As David says, what you want is wormhole for the funder to know the contributor is going to do that good and so fund it. Or, easier than a time machine, what if there was a class of investor looking to catalyze public goods at a lower or equal rate to what the ultimate benefactor would be. This might be a step towards that composability idea: the primary philanthropist could buy the right to say they enabled that public good to be created. Beyond the temporal dimension, Impact Certificates may also help with breadth of discovering good uses of funding.

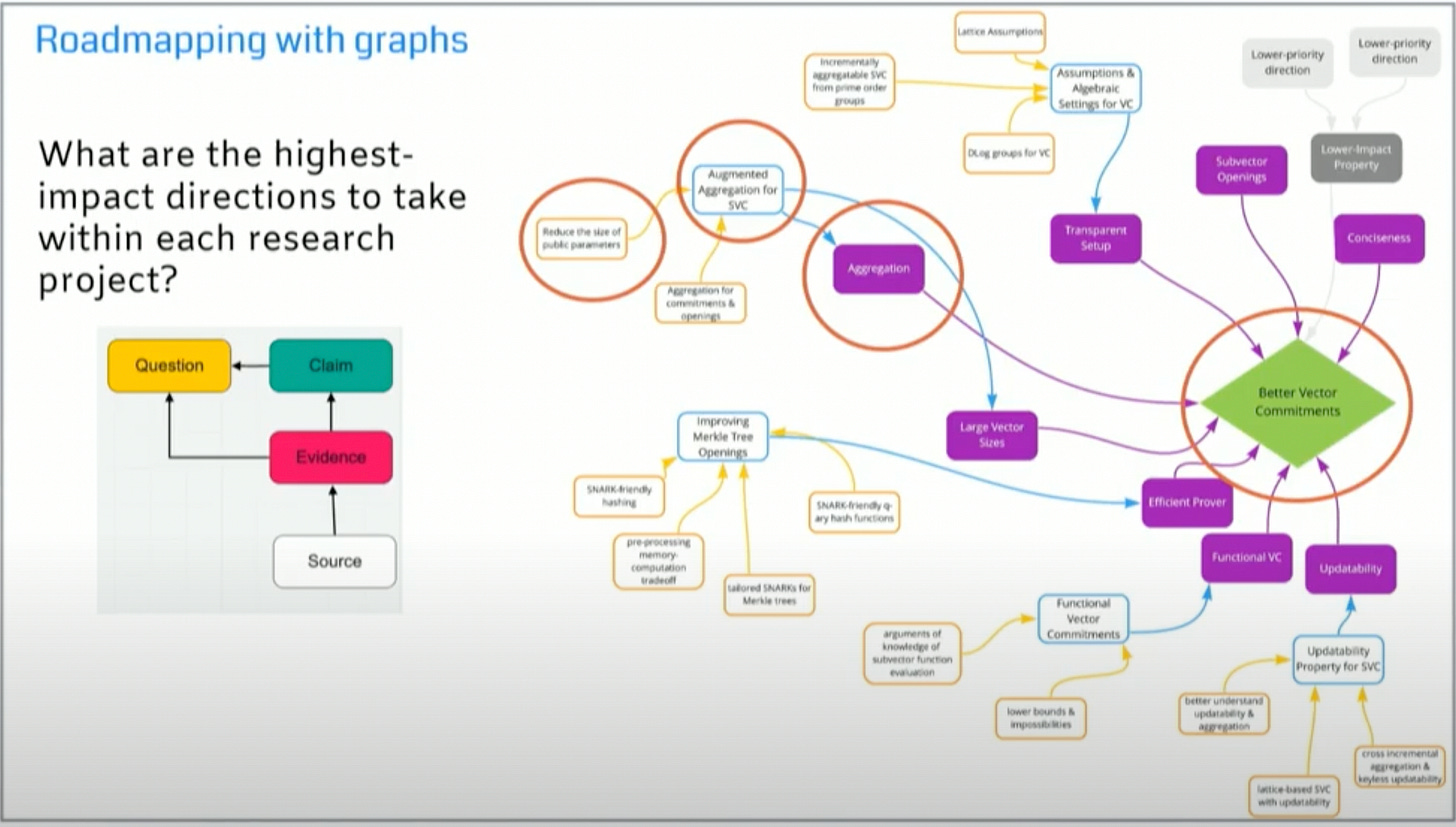

Karola Kirsanow articulated the frontier of graph-based roadmapping in her FTC22 talk, which seems to have a natural future integration with Impact Certificates. Roadmaps are of particular interest in neuroscience and climateTech, where most of the problems are enormous and complex. For examples on roadmapping, refer to TheClimateMap or this recent perspective paper on mineralization for carbon capture with the biotech section led led by Paul Reginato. So, in Karola’s talk, she presents the idea that if you have a knowledge graph, and a data model for a scientific process within a node in that graph3, the marketplace for funding could be built directly into the frontiers that graph. That’s a really big idea.

So here’s the hard part: details. What the heck does this actually look like in practice? For this post, I only want to sketch some thoughts of what Impact Certificates might look like in the context of funding biotech projects for the public good of the environment.

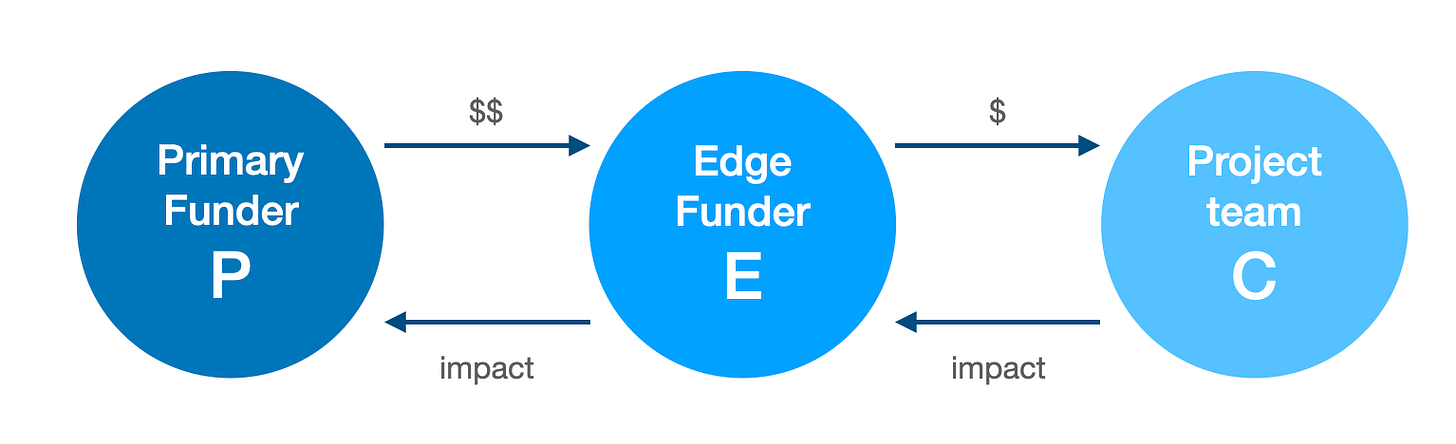

Let’s think through the simplest example. Assume you have a Project C, funded directly by an Edge Funder4, which distributes funds from Primary Funder P. To make this example tangible, let’s assume C is a bioengineering research effort toward a scalable carbon capture approach. For Project C, the core research risk is harnessing a previously difficult-to-engineer organism, and if the risk is overcome, there is a highly fundable larger project (or company) to be built. The interactions look like this:

So, if I understand the vision of Impact Certificates, the perfect world scenario is Project Team C does amazing work and the corresponding impact certificate becomes something worth transferring. Project Team C’s success at de-risking their effort makes them eligible for other existing sources of capital, which means the funding behind Team C was additional. Other Funders are now interested in purchasing ownership of the Impact Certificate for Project Team’s C initial project from Edge Funder E. This purchase of the Impact Certificate effectively frees up Edge Funder E to now make more public goods investments in the future5.

Even in that perfect world scenario, it raises a lot of specific questions. Below are my top 6 questions with some possible answers.

When is the impact certificate granted? A stock certificate would be upon the transaction of cash from the VC to the startup, so let’s assume the default answer is an impact certificate would be created upon Project C’s funding from the Edge Funder.

Who validates the things that Project C or the other owners of the Impact Certificate claim happened? The simplest answer is there is no automated validation at all, and any buyer protection is the responsibility of the people who transact in impact certificates. People who buy stock certificates are expected to do their own research but rely on basic conventions of good corporate behavior. So it may be possible that procedural validation of the Impact Certificate might be in everyone’s best interest: consider the damage of fraudulent pumping of the impact6 by any of the parties involved. Or, if we revisit the toy example above of Gates Foundation trying to deploy $1BB across multiple steps of organizations for malaria, some validator would be an essential piece of the Impact Certificate ecosystem.

Would it have the same feeling of philanthropic success for a Primary Funder to re-purchase the Impact Certificate from something they did not originally fund? This is a core assumption behind the idea of reselling Impact Certificates and could be validated by conversations and prototypes. Say Project C becomes a breakthrough in climateTech: Edge Funder E would be incentivized to sell their Impact Certificates in order to then fund future Projects F, G, H… But would it appropriately match the mandate of a major foundation like the MacArthur Foundation or the Simons Foundation to repurchase Project C’s Impact Certificate? In 2022, my guess is the answer is generally no, but it may be meet the needs of focused efforts. For example, Stripe has done great work in funding carbon capture efforts, perhaps they would repurchase the Impact Certificate for Project C with the intent of freeing up Edge Funder E to make their next bet.

What details need to be published in the Impact Certificate? If the impact certificate is indeed funded at inception (question 1), then the details of the project would basically be the grant application that acquired the funding. This is somewhat unsatisfying because the most interesting details will come from the development of the project, but that would require updating the Impact Certificate, which may be undesirable.

What if Project C becomes a company? Say in two years the team behind Project C makes a huge leap forward, how can that leap be attributed to the original impact certificate? While it sounds shiny to think “woah maybe an Impact Certificate could convert into a stock certificate!” that feels very difficult and very complicated. I think the answer has to be to stay as absolutely simple as possible, in which case there is no formal arrangement for Impact Certificates V1 to have anything to do with downstream IP or commercialization.

Who benefits from Impact Certificates? Funders. Primary Funders with a clearly articulated target portfolio of impact might like the ability to observationally de-risk projects before “retrocausally” funding them (David Dalrymple’s word). Edge Funders would love Impact Certificates because the new marketplace would allow Edge Funders to exist. And, maybe, the Project teams would also like the Impact Certificates as presumably they would hold on to some fraction of that ownership too.

Are there any precedents it Impact Certificates? At first glance, it feels roughly most similar to the Carbon Credit marketplace. The Carbon Credit marketplace can be a rough comparison: at its worst, Carbon Credits are murky, filled with scams and unintended backfires. However, failure in practice is not proof of flaws in the theory and successful carbon credit system could be one of the biggest levers we have in mitigating climate change. Failures aside, there is a reason huge amounts of money is flowing into the Carbon Credits, hopefully soon to be followed by substantial innovations in supply, demand and market security (eg, verification).

So I leave the reader with open questions about Impact Certificates. Would you accept funding that came with an Impact Certificate? Would it have any effect on your feelings around the funding and your publishing strategy? Are there exciting frontiers or fearful pitfalls you see in this idea?

The top VC funds have returned famously

epic IRRs, but keep in mind that the power law of returns applies to VC firms just as much as startups. The median return of a VC fund is probably closer to breakeven (see this 2012 analysis). What matters in this context is that the best VCs have built and shaped industries that became significant fractions of the modern economy.

Please note: I’m making this up as an illustrative example. I do not know much about malaria-related philanthropy.

Karola references the work of a Matthew Akamatsu, a professor at UW of biology, who is working to extend the idea of Discourse Graphs into Results Graphs.

“Edge Funder” is a made-up term, used in reference to the edge computing paradigm from the field of cloud computing.

Primary Funder P and Project Team C retain their own fractional ownership of the Impact Certificate, which now has some demonstrated value. But in my opinion there would need to be a pretty big cultural shift for either entity to also want to sell their Impact.

Consider the situation in which an Impact Certificate is purchased by a bad faith actor who then embarks on a marketing push to hype the value of Project C. The individuals most harmed by this would be the scientists who actually did Project C, because now their reputation is under threat from someone they have no control over.