Developing the Problem-Centric Founder

It's the right time to break away from today's entity-focused economy that shuttles all science into either academia or startups.

We can create more options for science founders.

Right now, every visionary scientist is forced into either academia or startups. These are the only repeatable methods we have1. This is a duopoly and the harm is that many great talents are robbed of agency or get locked into malformed startups. The benefits of creating more paths is that a whole latent class of talent, the scientist-founder, can be unlocked.

I can critique both academia and startups because I’ve done my time in both. I also love them both: Universities are the reason that I’m an American (my parents came here for my dad’s PhD) and co-founding a startup has been the most rewarding parts of my career. But, I’ve also seen the dark sides of both: I’ve seen my postdoc friends go through 200 faculty applications only to arrive in an impossible academic culture of trudging to tenure through awful administrative muck, and I’ve seen wonderful startup founders get permanently warped by getting stuck in a zombie2 company that takes five years to die.

We can show love to startups and to universities by giving them viable competition. And I think this is a special time to invent a third option.

About today’s duopoly

Startups are the best wealth creation vehicle humanity has invented and the university is the best knowledge creation vehicle humanity has designed. But that doesn’t mean they perfectly span the innovation space. Startups are best suited to scaling technology, not addressing a science risk. Similarly, universities are designed to train talent, not deploy talent3. We need to stop wedging every idea immediately into one of two tracks: let’s call the status quo the entity-focused mindset.

What we want, instead, is a third path in the innovation economy for a hotshot researcher to entirely pursue solutions to a big problem. Let’s call this the problem-focused mindset. In this new path, it’s the problem that matters, not the entity that initially receives the money.

If you’re an ambitious scientist today and you need funding for your big idea4, you have your choice of two entities to house your work. You can go academic, and the great thing about this path is that the money can be “free5,” it just takes a long time and is constrained by specific grant opportunities. On the other hand, you can call yourself a startup and the immediate benefit is it’s always open season for savvy investors: if they’re convinced you can make them money, they’ll fund anything quickly.

In the perfect world, addressing science risk is supported with the terms of the NSF but at the speed of venture capital.

Yes I’m being idealistic but we are making progress toward this vision. The best repeatable solution we have today is to support a scientist-founder type with a Fellowship6. But fellowships are cyclical and scope-constrained. For example, In my domain of climate biotech, Activate is a best-in-class fellowship. But this playbook generally funds individuals, not teams (although I hear Activate is innovating new offerings for the teams too). And the Fellows are still post-docs at universities because there’s no place else to do that research. Tackling science risk still hasn’t fully learned from Silicon Valley’s model of excellence.

Science needs can replicate what makes startup world so great: a big network of small teams operating with freedom, a spirit of collaboration and efficiently funded risk. Founders of these teams help each other in ways that are unique to founders, such as tactical support, emotional support in the hard times, trust to create joint ventures, recognition in the good times. These network effects are tangible, substantial and have been well-studied for years (eg, Professor AnnaLee Saxenian’s 1995 essay on the community effect in Silicon Valley has durable wisdom). And I’m seeing the early stirrings of a new founder community, but they’re not founders of venture-backed startups nor professors. They are a new breed of problem-focused, rather than entity-focused, founders.

Let’s land these meta thoughts with an illustrative example.

A quick founder narrative

Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.

- Henry FordAny scientist can have a check for any project they want so long as I look cool for investing in them for one year and I make my money back in four.

-The Average VC

You are a black-belt level biologist who can genetically engineer anything with time and money.

Let’s say you go deep into biomanufacturing and come out the other side thinking it’s insane that we’re pushing yeast and ecoli so far beyond their ideal. As Adam Marblestone puts it, you wouldn’t get a cat7, no matter how genetically modified, to pull a plow, so why do we accept this mistake at the microscopic level?

So you talk with the best people in the world and realize that, hey, with us working as an elite team, we could solve a set of common problems that could increase the speed of accessing *all* new microbial hosts, not just cherry picking from ones that happen to be convenient. It could be a major unlock for biotech. That’s a sweet mission!

You go talk with some venture capitalists. Look at my team, you say, we’re the best in the world at unlocking new microbial organisms for the trillion-dollar bioeconomy. “Ehhh,” the VCs say, “What market are you going after? What is the exit strategy?”

And you get frustrated because you’re speaking different languages with your Patagonia-vested tablemates. You are flapping your arms saying there is a clear bottleneck in the field of practice, look at all these famous names confirming the problem we need to solve. The money people are saying “yeah but this SaaS+climate company only has some marketing risk whereas you have worse than engineering risk, you have SCIENCE risk, on TOP of your market risk.”

But maybe you’re winning authenticity points by your persistence, so the funder leans forward on their All Birds and says, “OK, fine, how long do you think it’ll take to reach your first milestone?” to which you earnestly say “Just five years!”

Meeting(s) adjourned.

But, let me tell you that this outcome of rejection is FAR better than another world in which you’re stapled to a sinking ship.

The nasty ending is in the world in which you DO take the money. You fudge a few numbers (“Did I say five years? Oh no I mean two!”). You and the team sprint all-out to the first market opportunity and drift away from the core mission of unlocking novel microbes for everyone. You Google “how to make a business plan,” find out that vanillin seems to have a really high price and a reasonable volume, so you bail on your dream to take a short detour to profitability.

Your mission-driven team is now pretending to be market-driven mercenaries sprinting for some product nobody cares about. You keep telling yourself that “once we reach profitability, then we will be free to go back to our original mission of unlocking biology for everybody.” You limp over the finish line of the first milestone, raise a bit more cash, then finally get to market to learn that buyers of vanillin won’t pay what you’d hoped. Turns out that vanillin is easily detectable as synthetic by carbon isotope analysis and synthetic vanillin is worth a fraction of plant-based vanillin. You now have zero product, zero mission and have lost control of your company due to the terms of your latest funding round. Welcome to startup hell, you are a zombie company that won’t die until your investors say so.

But, thankfully, in this world, you did not take the VC funding. You did not over-rotate on some prestigious yet underqualified advice. You pushed and you pushed and you pushed and you found funders who understood that you are working to solve a problem first and foremost. Instead of small money from VCs that could have turned you into a zombie, you raise serious money from philanthropy that empowered you to create Cultivarium.

In this better world, you are Henry Lee and Nili Ostrov. And you are having a lot of fun doing your science at a scale far beyond that of a professor and with the freedom to steer directly into the science risk that a startup couldn’t stomach.

How do we get more positive examples like this? How do we get more world-class talent to stay true to what they KNOW is the most important problem that needs solving? How do we build an ecosystem of peers, funders and victories?

We’re in era of rapid evolution for how and where we do science

Cultivarium is a Focused Research Organization (FRO). A FRO is a new type of organization designed to operate on the order of a ~5-year, ~$50M time scale. This scale of project was crafted carefully to address a specific gap articulated through extensive enthnography of big-thinking scientists. Today, Convergent Research is the primary developer of FROs, but in principle, anybody can set up a FRO-like entity. These are, by default, non-profit entities that are solving a scientific problem. As there are now multiple FROs that are attracting top talent and philanthropic partnerships, we can say that FROs are the first substantial entry into the problem-centric playbook.

But I’m seeing a strange glitch that’s forming: I now have conversations all the time that sound like “Can you check out my FRO proposal?” What I’d prefer to hear is “Can we discuss this important problem that I think I can solve?” That is, the launch of FROs substantially shifted the Overton Window of what scientists dream is possible (this is an enormous step forward for scientific culture). But, there is now a over-rotation in trying to make everything sound like a $50M, 5-year project, which is getting people sucked back into the entity-first mindset.

A team of three scientist-founders pitching a $50M FRO is pretty similar to a team of three technology-founders pitching a Series C company before they’ve written a line of code. Only in rare situations is this a serious proposition: discovering and cultivating these teams is what makes Convergent special.

So as the problem-focused economy grows, it will become less discrete and more continuous. If a FRO is a $50M organizational structure, then the natural question is to ask what the $5M organizational structure is, or even what the $500k structure. Can there be proto-FROs to derisk core elements of something that becomes full FRO? This begins to feel like startup funding rounds, and this is a good thing. Funding rounds are the natural mapping of money into progress, there needs to be a continuous growth path for all problem-centric efforts to sit on.

So if we are to take the best from the Silicon Valley entity-centric founder and map it into the problem-centric founder, we would see the following:

Science-risk can be tackled by using non-dilutive funding to allow the problem-centric founder to steer right into the biggest challenge. This is still driven by milestones but allows operational flexibility until the best entity to support the effort becomes clear.

Fast funding decisions made in weeks not years, in open scope with value-add funders. I talk trash on VCs because most of them are useless. But the great VCs are undeniably excellent catalysts, mostly because they were once leaders of significant efforts themselves.

Network effects of small teams on comparable trajectories evolves into repeated pathways to success. This includes a common, minimal legal structure and funding terms that all teams follow.

A broadening funder base that understands the milestones of the science and trust in the early stage funders. High-brand early checks from Y-Combinator, Activate or Breakthrough Energy Fellows are powerful indicators that entice the future funders to an organization.

Building a growth model for problem-focused founders

“Every non-profit should be constantly trying to put itself out of business.”

-Isha Datar, Executive Director of New Harvest

I never expected to be a non-profit founder. Yet here I am, because my co-founder Paul Reginato, and growing team, and I are working to solve what we think is the most important problem: only a fraction of biotech’s potential is being deployed to climate because of opacity of important challenges and the siloed best efforts. To do our best work, Homeworld needs to be a non-profit just like World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has to be a non-profit to serve the internet.

When I was a software startup founder, it was because I set out with the intention of founding a startup and we discovered a problem worthy of that entity. But, in contrast, our road to Homeworld Collective was through complete commitment to a problem, the entity came later. By being focused on the mission of growing the field of climate biotech, the non-profit formulation was built around us.

It’s not easy to be a problem-focused founder building a non-profit and I’m very blunt that it took us much longer to raise funds than I expected. Even though we had a clear problem to solve and the authenticity to be the team to solve it, it still took us a long time to raise support for Homeworld Collective. Soon, I hope problem-focused playbook will become more codified, but for now, I think I can do some service by sharing my mental models with the community.

The linear order:

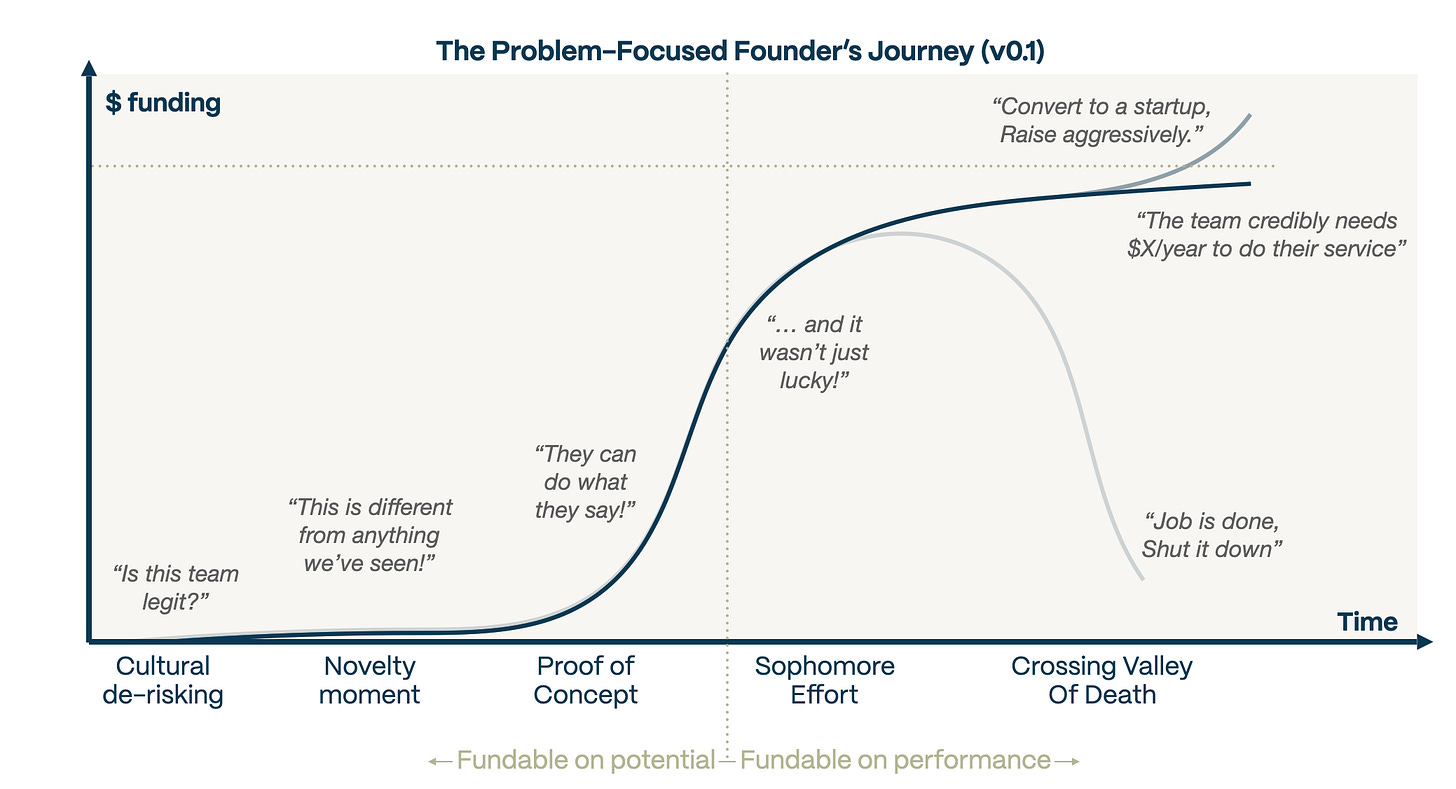

Here is my developing mental model of the arc of funding a problem-centric founder (see image above). If you go the non-profit route, here are the steps I think you’ll go through:

Cultural De-Risking. You need to get on the map of funders as a trustworthy and compelling leader. Reputation and legal compliance are of utmost importance to philanthropies, and they have a high noise floor of spammy inbounds.

Novelty Moment. You’re doing something radical and beautiful and you’re telling a story that it can’t be done anywhere else but in a non-profit. This is a great time to raise your equivalent of a seed check.

Proof of Concept. You have shown the world that you can actually do something substantial in accordance with your mission and theory of change. You now need to fundraise in preparation for the upcoming Valley of Death.

Sophomore Effort. You show you can do it twice, bigger and better. This is important evidence that you are scaling your solution in accordance with your theory of change, and that you are credible to raise larger funds.

Valley of Death. You are no longer the shiny new thing, you need to be the performing-exceptionally-well thing.

Three endpoints:

Science is done, published (and all other necessary compliances), and now a startup is the entity to continue solving the problem.

The Valley of Death was successfully crossed and on the other side is reputable non-profit with a strong reason to continue existing.

The Valley of Death was not crossed and the non-profit is sundowned.

Today’s conclusion: the TBD-Corp

If you're going to try, go all the way. There is no other feeling like that. You will be alone with the gods, and the nights will flame with fire. You will ride life straight to perfect laughter. It's the only good fight there is.

-Bukowski

I’m not against startups, I’m against bad startups. I’m not against academia, I’m against academia when it becomes academentia8.

In the future, I think all efforts facing a science challenge would be better off de-risked through standardized, scientist-friendly non-dilutive terms. We have B-Corps, C-Corps and S-Corps, why not have a TBD-Corp? You raise money in a repeatable form (eg, through a common fiscal sponsor) to get the first bit of progress to solve your problem. If the science looks like it’ll work but will take awhile, you use the evidence you just created to make a research non-profit. Or, if the science worked quickly and you can see a path to market, go straight to build a startup. And if neither the team nor the science works, open source your results and take the W of discovering a true negative.

If done right, this protects and leverages the most important resource: the time capital of our best scientific talent.

A handful of startup funds already do a subtle combo of philanthropy and venture capital this in their own bespoke ways: but it’s generally not publicized. We are still waiting for the “Y-Combinator moment for science,” which will look like standard terms, standard growth playbooks and funders lining out the door to hear the demo days. When this moment comes, the wilting monocrop of the academic status quo will be overrun by a vibrant ecosystem which grows taller and mightier than its predecessor.

See you at the TBD-Corp incubator!

Resources

Homeworld sits inside a growing pool of peer organizations: Spark, Spectech, New Harvest, Good Food Institute, TripleHelix, Norn Group (creators of Impetus Grants), Experiment.com, Two Frontiers Project, Future House, Align to Innovate, TechMatters, Roots of Progress, Convergent Research, Cultivarium, E11, [c]Worthy, BitsInBio, OpenBioML, and so many more.

1517 Flux Capacitor’s approach to funding early projects with $100k on favorable startup-like terms (announcement), which might be the best instantiation of the “TBD-Corp” that I’ve seen.

Strong recommendation for Erika DeBenedictis’ blog, specifically Quick Start Guide to Research Non-Profits.

Sam Rodriques from FutureHouse also just published this commentary in Cell.

Seemay Chou and Prachee Avasthi are doing awesome work Arcadia Science, for example, their publication model of their team science is radically different.

SpecTech’s BRAINS accelerator is a fantastic first example of cultivating this talent.

“A Vision of Metascience” by Michael Nielsen and Kanjun Qiu. A monster read filled with deep thinking.

Novo Nordisk created the BioInnovation Institute (BII) which offers founder-friendly investment terms that are, as I roughly understand it, a grant that converts into a loan if the project takes form.

I generally advise everyone to read Ben Reinhardt from SpecTech, Jason Crawford (great recent piece on evolvable science institutions) from Roots of Progress, and follow Sam Arbesman’s Overedge Catalog and read Nadia Asparouhova’s writings.

Derek Thompson’s 2021 piece America Needs a New Scientific Revolution remains one of my top references.

Jonathan Wosen has been doing some excellent writing on top researchers leaving university, eg Life scientists’ flight to biotech labs stalls important academic research.

David Lang does some of my favorite applied work to empowering scientists to ScienceBetter. He has a great recent piece on the unreasonable effectiveness of small grants and one of his great essays is the Hollywood Analogy

Acknowledgements:

Thank you for helpful conversations and feedback. In random order:

Kenza Samlali, Seemay Chou, Erika DeBenedictis, Pritha Ghosh, Ben Reinhardt, Paul Reginato, Ariana Caiati, Paul Himmelstein, Henry Lee, Niko McCarty, Jim Fruchterman, Jasnam Sidhu, Erin Smith, Devika Thapar, Mark Hansen, Dan Voicu

The duopoly framing ignores the role of corporate research and development labs, which do make significant contributions. I did so because I’m interested in the repeatable tools for “zero-to-one” efforts like the SAFE note or like Y-Combinator-esque incubator, that could be repeated by any community.

A zombie company is one that is doomed but cannot be shuttered because the founders have lost control, so they limp towards a lame death 3-5 years later than needed.

I think it was Chris Eiben who one day made the relevant quip, “The straw is the best tool to drink my milkshake, but the worst tool to eat my spaghetti.”

A good idea is a good problem paired with a good solution. This is important to remember, as they are many amazing solutions for unimportant problems. While I often fanboy on Hamming and Hilmeier for their work on problems, Michael Nielsen surfaced this wonderful letter from Feynman on problems.

Ignoring future IP and other spinout baggage from universities.

Or maybe an SBIR, although there are stories of the “SBIR Trap”that can take years for relatively little money.

With the possible exception of this myostatin-deficient cat

I’ve now also heard “academenial”

Strong resonance with us! Thanks for writing this!

Good post! Thanks for the shout-out, here is an older post of mine that is even more directly relevant: “while science and business have functioning career paths, invention today does not” https://rootsofprogress.org/a-career-path-for-invention